A theme we [want to explore] is “complaining & blaming.” I thought it would be a useful theme because our culture tends toward complaint. If I’m suffering, then the way to the end of suffering is to complain or blame. I’m suffering, therefore it’s somebody else’s fault. I’ve been treated unfairly. This isn’t right. It shouldn’t be this way. This is powerful conditioning in our lives. I remember a New Yorker cartoon with a student asking a monk, “You say life is suffering, but isn’t it also complaining?” It’s useful to take a period of time to reflect on the unconscious or semiconscious way we react to the experience of suffering—to reflect on the urge to be critical, to be negative, to complain, or to find fault in ourselves or in the things around us. While reflecting like that, we can broaden our view by inquiring into the matter. Why do I think I shouldn’t have to experience this illness, this pain, this weather, this food, this person sitting next to me?

If I’m suffering, then the way to the end of suffering is to complain or blame. I’m suffering, therefore it’s somebody else’s fault. I’ve been treated unfairly. This isn’t right. It shouldn’t be this way. This is powerful conditioning in our lives. I remember a New Yorker cartoon with a student asking a monk, “You say life is suffering, but isn’t it also complaining?” It’s useful to take a period of time to reflect on the unconscious or semiconscious way we react to the experience of suffering—to reflect on the urge to be critical, to be negative, to complain, or to find fault in ourselves or in the things around us. While reflecting like that, we can broaden our view by inquiring into the matter. Why do I think I shouldn’t have to experience this illness, this pain, this weather, this food, this person sitting next to me?

Then we can broaden our view further by consciously evoking a sense of appreciation & gratitude for the gifts & opportunities we have in our lives. This is a way to catch the mind’s habitual movement toward criticism or complaint, its movement toward the classic glass-is-half-empty attitude. Evoking gratitude goes directly against that complaining, criticizing, blaming mind. But we need to make sure that this gratitude isn’t based  on a “think-pink” attitude—trying to sugarcoat things & pretend that we’re not really feeling critical or negative. It doesn’t help much to paste an artificial expression of gratitude on top of a negative mood or a feeling.

on a “think-pink” attitude—trying to sugarcoat things & pretend that we’re not really feeling critical or negative. It doesn’t help much to paste an artificial expression of gratitude on top of a negative mood or a feeling.

We begin with listening to the critical, blaming, or complaining mind, and hearing what that mind is saying. What’s it coming up with? Is it the feeling of being unfairly treated, slighted, left out, or ignored? Can we hear the mind’s cry of righteous indignation, So what am I, chopped liver? We receptively listen to the affronted, hurt, wounded, abandoned, irritated feelings, and hear the mind coming up with the reactions & thought processes that follow those feelings. We are simply allowing this experience to be known—this narrow, painful, reactionary state of complaining or feeling slighted. By bringing awareness to that, fully knowing its reactive quality, we can recognize & inquire, This is a really painful state. Why would I choose to react like this? Why would I want to carry this around & burden my heart with this? We’re not saying to ourselves, Oh, I’m supposed to be grateful now, I should plant some gratitude in here. Instead we are simply seeing the painfulness of our narrow, self-centered reactions. Once we see this, then the very acknowledgment of that painfulness can enable us to let go & relax. In the broadening of our views & attitudes, what arises is gratitude. We are able to appreciate the bigger picture, the gifts and the lessons we have received, and the potential opportunities we have in the world.

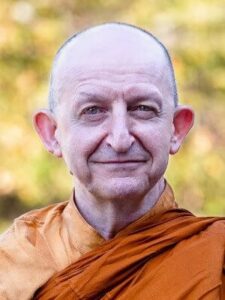

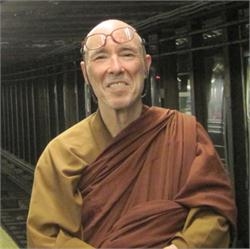

Ajahn Amaro is abbot of the Amaravati Buddhist Monastery in England, a center inspired by the Thai Forest Tradition & the teachings of the late Ajahn Chah. This reflection is from the book Beginning Our Day, Volume 2, published in 2008 when Ajahn Amaro was co-abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery in California. He has written a number of books, including an account of an 830-mile trek across England from Chithurst Monastery to Harnham Monastery called Tudong, the Long Road North.

the teachings of the late Ajahn Chah. This reflection is from the book Beginning Our Day, Volume 2, published in 2008 when Ajahn Amaro was co-abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery in California. He has written a number of books, including an account of an 830-mile trek across England from Chithurst Monastery to Harnham Monastery called Tudong, the Long Road North.

It’s that time of year…. at least here in the Northern Hemisphere. Springtime, this season of replenishment when the natural balance, reciprocity & generosity of spring is a mirror for our own re-flourishment after more than a year of what many people have experienced as a deep or at least a partial drought of the reciprocity of connection, mutual flourishing, replenishment & in-person generosity.

It’s that time of year…. at least here in the Northern Hemisphere. Springtime, this season of replenishment when the natural balance, reciprocity & generosity of spring is a mirror for our own re-flourishment after more than a year of what many people have experienced as a deep or at least a partial drought of the reciprocity of connection, mutual flourishing, replenishment & in-person generosity. pleasant or unpleasant, with the trust that it is just right, just enough for our spiritual growth to unfold. We can give ourselves the gift of truly learning to be in the present moment with clear mindful awareness… receiving the present moment with gratitude, appreciation & humility. We can learn to apply the wise attention of mindful awareness in the midst of any exchange, any relationship, any emotional state, any sensation that moves through our body… to the smell of rain, the touch of the wind on our skin, to tending of each & every plant in the garden & filling the bird feeders, to any task we might be engaged in, to the experience of a breath from its birth all the way through to its death.

pleasant or unpleasant, with the trust that it is just right, just enough for our spiritual growth to unfold. We can give ourselves the gift of truly learning to be in the present moment with clear mindful awareness… receiving the present moment with gratitude, appreciation & humility. We can learn to apply the wise attention of mindful awareness in the midst of any exchange, any relationship, any emotional state, any sensation that moves through our body… to the smell of rain, the touch of the wind on our skin, to tending of each & every plant in the garden & filling the bird feeders, to any task we might be engaged in, to the experience of a breath from its birth all the way through to its death. Zen master Dogen was once asked: “What is the awakened mind?” He replied: “The mind that is intimate with all things.” In meditation we spend a lot of time observing both mind & body through the simple process of connecting directly with the ongoing flow, the flow of our experience, and as our practice deepens, so does intimacy.

Zen master Dogen was once asked: “What is the awakened mind?” He replied: “The mind that is intimate with all things.” In meditation we spend a lot of time observing both mind & body through the simple process of connecting directly with the ongoing flow, the flow of our experience, and as our practice deepens, so does intimacy. One of the hardest things for us to learn in meditation is that this practice is not about having certain kinds of experiences or attaining special, blissful, or peaceful states. Of course, sometimes we do have what we might call special experiences, and there is nothing wrong with having them. They may serve us by bringing energy & interest to meditation but if we focus on them too much they may just get in the way. What we are interested in exploring are the universal characteristics or qualities that apply to all things – to any & every experience whether special or mundane, pleasant or unpleasant. We might call this the essential nature of all experience.

One of the hardest things for us to learn in meditation is that this practice is not about having certain kinds of experiences or attaining special, blissful, or peaceful states. Of course, sometimes we do have what we might call special experiences, and there is nothing wrong with having them. They may serve us by bringing energy & interest to meditation but if we focus on them too much they may just get in the way. What we are interested in exploring are the universal characteristics or qualities that apply to all things – to any & every experience whether special or mundane, pleasant or unpleasant. We might call this the essential nature of all experience. way. Mindfulness has the power to transform perceived obstacles to meditation into objects of meditation. With mindfulness practice there is the implicit understanding that if it is in the way, it is the way. This understanding is not only a great relief, it is also empowering because it relieves us of the need to spend our time & energy in the futile attempt to control our experience.

way. Mindfulness has the power to transform perceived obstacles to meditation into objects of meditation. With mindfulness practice there is the implicit understanding that if it is in the way, it is the way. This understanding is not only a great relief, it is also empowering because it relieves us of the need to spend our time & energy in the futile attempt to control our experience. nd setting off into the simple and austere life of a renunciate. When I take a moment to slow down and imagine this kind of radical life change, I think, “Wow, to begin such a journey requires a deep and profound passion.” In this way, I have noticed when I am skillfully passionate about my own spiritual journey, deeper dimensions of the Dharma are revealed. I experience a yearning that carries me out the gates of my own “palace” and leads me onto the path of awakening.

nd setting off into the simple and austere life of a renunciate. When I take a moment to slow down and imagine this kind of radical life change, I think, “Wow, to begin such a journey requires a deep and profound passion.” In this way, I have noticed when I am skillfully passionate about my own spiritual journey, deeper dimensions of the Dharma are revealed. I experience a yearning that carries me out the gates of my own “palace” and leads me onto the path of awakening. he “palace.” I hadn’t fully developed the skill of yearning that would carry my spiritual practice forward once I’d left the monastery.

he “palace.” I hadn’t fully developed the skill of yearning that would carry my spiritual practice forward once I’d left the monastery.

p recedes. Even if we were to reach the top, it can lead to craving for the next mountain or for a return to the “palace.”

p recedes. Even if we were to reach the top, it can lead to craving for the next mountain or for a return to the “palace.” Through effort, attention,

Through effort, attention, something more important: a strengthening of the inner qualities that sustain a spiritual life for the long term: mindfulness, persistence, courage, compassion, humility, renunciation, discipline, concentration, faith, acceptance & kindness.

something more important: a strengthening of the inner qualities that sustain a spiritual life for the long term: mindfulness, persistence, courage, compassion, humility, renunciation, discipline, concentration, faith, acceptance & kindness. Meditators all too often measure their practice by their “meditative experiences.” While a range of such potential experiences can play an important role in Buddhist spirituality, day-to-day practice is more focused on developing our inner faculties & strengths. This includes cultivating awareness & investigation in all circumstances, whether the weather is clear or stormy. A wealth of inner strength follows in the wake of mindfulness & persistence. Such strength is often accompanied by feelings of calm & joy; but, more important, it allows us to remain awake & free under conditions of both joy & sorrow.

Meditators all too often measure their practice by their “meditative experiences.” While a range of such potential experiences can play an important role in Buddhist spirituality, day-to-day practice is more focused on developing our inner faculties & strengths. This includes cultivating awareness & investigation in all circumstances, whether the weather is clear or stormy. A wealth of inner strength follows in the wake of mindfulness & persistence. Such strength is often accompanied by feelings of calm & joy; but, more important, it allows us to remain awake & free under conditions of both joy & sorrow. Before you know what kindness really is

Before you know what kindness really is

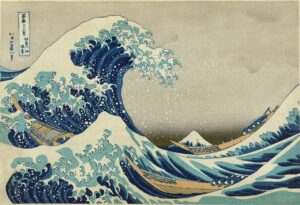

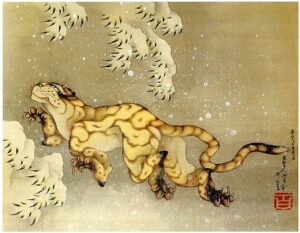

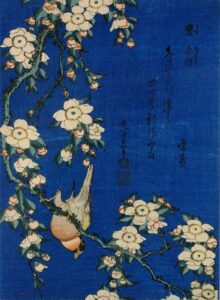

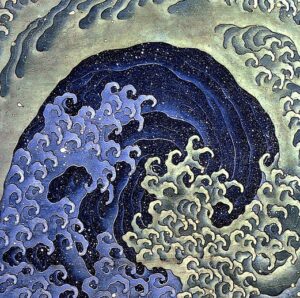

Hokusai says look carefully.

Hokusai says look carefully.

Everything lives inside us.

Everything lives inside us.

nown scholar-monk Bhikkhu Bodhi has collected & translated the Buddha’s teachings on conflict resolution, interpersonal & social problem-solving, and the forging of harmonious relationships in the 2016 book

nown scholar-monk Bhikkhu Bodhi has collected & translated the Buddha’s teachings on conflict resolution, interpersonal & social problem-solving, and the forging of harmonious relationships in the 2016 book  much of what he taught so long ago can be relevant to people’s lives today. The Buddha saw that people can live together freely as individuals, equal in principle & therefore responsible for each other.

much of what he taught so long ago can be relevant to people’s lives today. The Buddha saw that people can live together freely as individuals, equal in principle & therefore responsible for each other. to live more happily here & now….

to live more happily here & now…. Joy is wired into our genes, brain circuits & biology. It’s an integral part of our health equation. And in times like these, it matters more than ever.

Joy is wired into our genes, brain circuits & biology. It’s an integral part of our health equation. And in times like these, it matters more than ever. ve through acknowledging & honoring the goodness in our nature, our healthy humanbeingness. This nurtures our capacity to feel joy, happiness & delight in relationship to another’s happiness, success, health, brilliance & beauty, as well as delight in the magnificence of this planet & all the sentient beings who share it with us.

ve through acknowledging & honoring the goodness in our nature, our healthy humanbeingness. This nurtures our capacity to feel joy, happiness & delight in relationship to another’s happiness, success, health, brilliance & beauty, as well as delight in the magnificence of this planet & all the sentient beings who share it with us. in this immediate experience of presence, we are free to pour our energies into the activity of life itself… no comparing or competing. We’re free to purely rejoice in/with another being’s delight, success, health, brilliance & beauty.

in this immediate experience of presence, we are free to pour our energies into the activity of life itself… no comparing or competing. We’re free to purely rejoice in/with another being’s delight, success, health, brilliance & beauty. In the late 1980s, the Thai monk Ajahn Suwat was teaching a ten-day retreat at the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) with Ajahn Geoff (Thanissaro) as his translator. Ajahn Suwat had been in America for some time but he hadn’t taught a retreat to Westerners before. After several days, Ajahn Suwat asked Ajahn Geoff, “Why do the students seem so unhappy? They’re meditating. They’re here. But they seem so grim & not at all like they’re enjoying themselves.” After thinking about it, Ajahn Geoff said, “They know how to meditate, but not how to practice dana.” He saw a direct relationship between the lack of happiness & the lack of a foundation in dana.

In the late 1980s, the Thai monk Ajahn Suwat was teaching a ten-day retreat at the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) with Ajahn Geoff (Thanissaro) as his translator. Ajahn Suwat had been in America for some time but he hadn’t taught a retreat to Westerners before. After several days, Ajahn Suwat asked Ajahn Geoff, “Why do the students seem so unhappy? They’re meditating. They’re here. But they seem so grim & not at all like they’re enjoying themselves.” After thinking about it, Ajahn Geoff said, “They know how to meditate, but not how to practice dana.” He saw a direct relationship between the lack of happiness & the lack of a foundation in dana.

Ajahn Pasanno

Ajahn Pasanno